Australia need to call a doctor to remedy spin, not pitches

Australia’s Fox Sports media group accused India of ‘straight-up pitch doctoring’ a day before the Border-Gavaskar Trophy began. However, while the Indians posted 400 on the board in their only batting innings, all the Kangaroos managed was 177 and 91 respectively, resulting in a humiliating defeat.

Out of nowhere, the Nagpur wicket became the centre of attention even before the much-anticipated fixture between the two heavyweights commenced. Many well-known Australian media organizations, as well as their former players, involved themselves in constant negative chatter regarding the pitch. As a consequence, well pointed out by Brad Haddin, the tourists put their ‘energy into the wrong places’ during preparations by observing how Indian curators watered and rolled the track, and of course, paid the price for it later on.

It would suffice to say Australia’s pre-match strategies and plans got messed up by their heads in Nagpur. Barring debutant Todd Murphy’s brilliance and an almost season-long resistance from the world’s top two batters, Marnus Labuschagne and Steven Smith, they were uncoordinated and miserable throughout the two-and-a-half days of play. Unlike the happy memories they have enjoyed so far under Pat Cummins’ captaincy including a glorious Australian summer, there seemed to be no consistency or pattern in their team that they could hang on to keep themselves in the hunt.

So what went wrong for Australia in Nagpur where spinners took 24 out of 30 wickets? Must be something new to the world in terms of playing Tests in India. Well, no. Then what’s the fuss all about?

To be clear, whenever India produce rank turners at home – something they have been doing for ages to enhance their strength – they are subjected to a full-blown character assassination. On the other hand, when the other Godfather members of the ICC from outside the subcontinent come up with green tops to assist their potent fast bowlers, their criticism is limited to a slight whisper. Maybe this happens because the appearance of cracks on spin-friendly wickets over time makes the tracks look ugly whereas on green pitches, grasses take time to wear off before the spinners come into play, leading to more balanced affairs on occasion. Maybe all the cricket-playing nations are whingy teenagers struggling to come to terms with reality. Who knows?

This bizarre perception of the nature of pitches was the primary reason behind the ‘poor rating’ for the Pune pitch in the game between India and Australia. On the other hand, the Gabba pitch for the clash between Australia and South Africa only received a ‘below average rating,’ highlighting the contrast in perception. To be fair, even the Ahmedabad pitch which was used for the England fixture in March 2021 was not a good advertisement for the longest format of the game. However, the Nagpur pitch was nowhere near that vicious track, as admitted by Cummins himself after the game.

... the wicket spun but it wasn’t unplayable. We’d love to get another 100 or so runs and put a bit more pressure on their first innings.

Pat Cummins

Let’s get this straight. In Test cricket, bowlers win you matches and series, and at any time have to play more clinical roles than the batters to make it all happen. This is what worldwide appreciation for India’s bowling revolution in Test cricket under Virat Kohli was based on. By constantly backing fast bowlers to evolve, including the likes of Jasprit Bumrah, Mohammed Shami, Ishant Sharma, and Mohammed Siraj, Kohli enjoyed a record 40 victories in 68 Test matches, including two series triumphs each in New Zealand and Australia. Thereby, at this point, India have all the answers ready regardless of the challenge at hand. With Ravichandran Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, and Axar Patel already in the mix, their bowling attack often emerged as the superior one in any condition.

But then, why did the pitch debate begin in the first place? History. If you look back to the 50s, 60s, and 70s, England and Australia dominated the game before the West Indies started clinching all the headlines. Amongst the 18 bowlers in Test between 1945 and 1990 with over 200 Test wickets, only five were spinners. The record clearly indicates that fast bowlers ruled cricket for a lengthy period of time. Besides, suitable conditions in England, Australia, and the West Indies helped them to thrive even further until the legendary spin duo of Muthiah Muralitharan and Shane Warne came into the limelight and put up a fight against them.

![Bowlers who dominated Test cricket [Span 1945-90, minimum 200 wickets]](https://sportscafe.in/img/es3/articles/cricket-2023/creative_1-1000x1000.webp)

SportsCafe Graphic Team.

Bowlers who dominated Test cricket [Span 1945-90, minimum 200 wickets]

So what’s the problem with playing in different conditions? Isn’t it in the direction for the sport itself, or would you rather have Test cricket played continuously on similar sorts of pitches that primarily help fast bowlers? Or maybe the world wants more of dead Pakistan pitches with no grass or moisture as on display when England and New Zealand toured there lately?

Just a gentle reminder: there is nothing mentioned in the rulebook about how exactly the pitches should be prepared by the hosts.

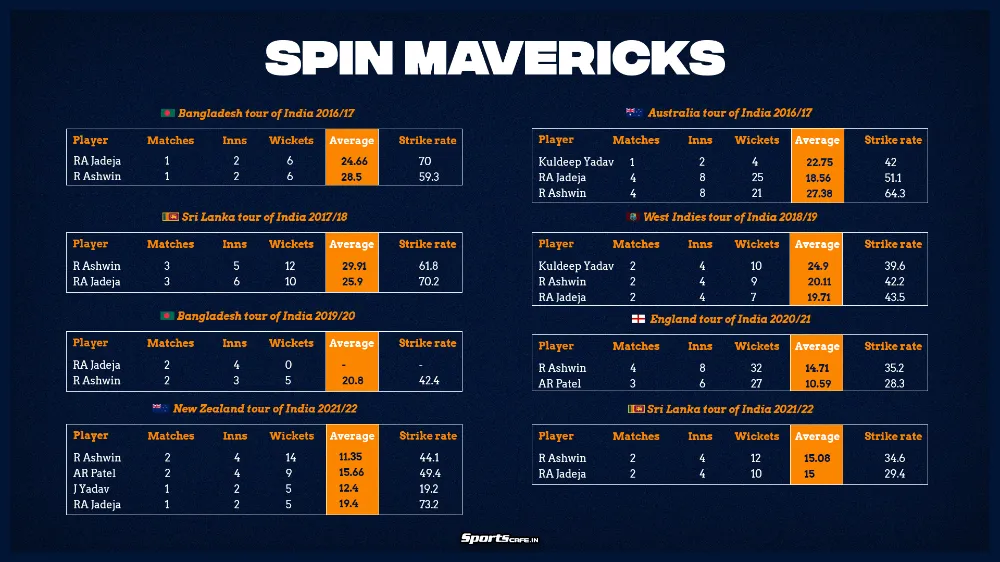

Even a look at how spinners have fared in India since Australia’s last tour of India in 16/17 suggests the hosts’ spinners have been successfully taking the bulk of wickets while the tourists, more often than not, have struggled to find any rhythm. Ashwin is well aided by either, or at times both, Ravindra Jadeja and Axar Patel in these conditions, while the likes of Murphy and Ajaz Patel receive little assistance from their teammates even if they find extra gear.

SportsCafe Graphic Team.

Indian spinners have always been impressive in local conditions.

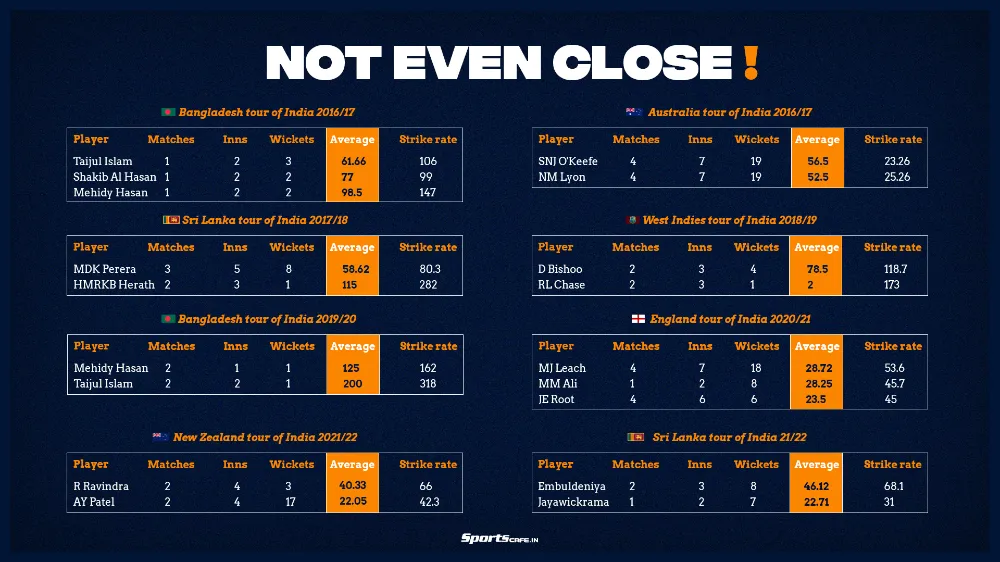

The problem for the visiting sides lies right there: lack of quality spinners who can bowl in tandem by adjusting to Indian conditions to keep snaring breakthroughs. The last time a tourist side successfully made it happen was during England’s tour of India back in 2012/13. In fact, in the series, Graeme Swann was the joint-highest wicket-taker, claiming 20 wickets in four matches at an average of 24.75, the same as Pragyan Ojha but at a worse average of 30.85. With 17 wickets from three games, Monty Panesar gave the support Swann required, which eventually culminated in a whitewash of India in their own backyard. Since then, the Men in Blue have not lost a single Test series at home, and fair to say, no pair has managed to pull off something as spectacular as what Swann-Panesar did. Even the greats Warne and Muralitharan had sub-par performances in India, taking 34 wickets from nine matches at 43.11 and 40 wickets from 11 matches at 45.45 respectively.

SportsCafe Graphic Team

Overseas spinners usually struggle in India more often than not.

There is no denying that India, traditionally, does not produce a pitch that has a high probability of running the entirety of five days. They will dry and crack, and one must prepare themselves to tackle those surfaces much like Rohit, Jadeja, and Axar in Nagpur. In 2017, Steve Smith’s gritty century in Pune in 2017 was highly lauded, largely because the pitch received a ‘poor rating’ later on by the match referee. This time around, however, there was a lot of noise around pitches even before the series began. The trash-talk particularly did not allow Rohit’s splendid knock, as well as batting contributions from Jadeja and Axar, to get the praises they deserve. Therefore, visiting countries should focus on making their spinner capable enough of causing destruction with the ball in hand on Indian surfaces rather than making commenting comments in the run-up to face reality.

Comments

Sign up or log in to your account to leave comments and reactions

0 Comments