The story of how the Invincibles became the Invisibles in T20 cricket

I think it is difficult to play [T20 cricket] seriously - Ricky Ponting, 2005.

“We, in the ages lying,

In the buried past of the earth,

Built Nineveh with our sighing,

And Babel itself in our mirth;

And o'erthrew them with prophesying

To the old of the new world's worth;

For each age is a dream that is dying,

Or one that is coming to birth.” Arthur O'Shaughnessy's ‘Ode’, 1873

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Buchanan was saying: 'It's only a muck-around game, don't worry about it'. We trained for four hours on the morning. So we went from the nets next door, busting a gut, into a T20 game where they rolled up playing it like a Test match and flogged us.

Damien Martyn, 2005

This is a story of a change of guard. An all-conquering empire, consumed by its own arrogance, failing to keep up with the times. Just like the Romans’ self-indulgence in their own culture brought their demise. Or the way the Mughals failed to spot the incoming British barrage feigning the hand of friendship.

It was no secret that our attitude to Twenty20 cricket was undeveloped. As a group, we didn't think this tournament [ICC World T20 2007] was that big a deal.

Adam Gilchrist, 2007

Extinction and evolution is the way of life. When Darwin said it’s all about survival of the fittest, Australia were too busy sipping champagne bathed in glory. In the blur of success, they lost sight of the revolution that was approaching. A beast by the name of T20 that would take the world by storm. Afterall, what could possibly topple the Kangaroos’ brigade that had built the greatest empire in the history of the sport? If they wanted they could have captured Leningrad in the Russian winter and then invaded the Nanda Empire on the same night.

I'd like to be able to tell you that I knew what was going wrong [at the World T20].

Ricky Ponting, 2009

Yet, as it turns out, all it took was the raging popularity of the shortest format to make their other success seem immaterial, given the team’s failures in the commercial playground of our sport. Today, the Australian Cricket Team is as much a reflection of its legacy as an ostrich is of dinosaurs – supposedly evolved from the same genes, yet meek in the face of adversity.

Adversity was something the men from Down Under knew nothing about, or at least they made it seem that way. The side was filled with such quality players era upon era that over time it resulted in an unnerving self-confidence capable of taking down any rebel that dared challenge them. It did not matter whether it was the fearsome Pakistan pace attack in 1999 or a defiant India in 2003 – the Aussies were here to slaughter and win. If a Richie Benaud departed, Dennis Lillee was waiting in line. The Waughs gave way to the Pontings and Haydens of the world and the domination continued. From 1995 to 2005, Australia had an unfathomable winning percentage of 70 in ODIs, by far the best in the world. In fact, even during T20Is’ infancy, the Kangaroos managed to win two Champions Trophies, conquer the Test mace, and the 2007 50-over World Cup triumph was their third on the trot.

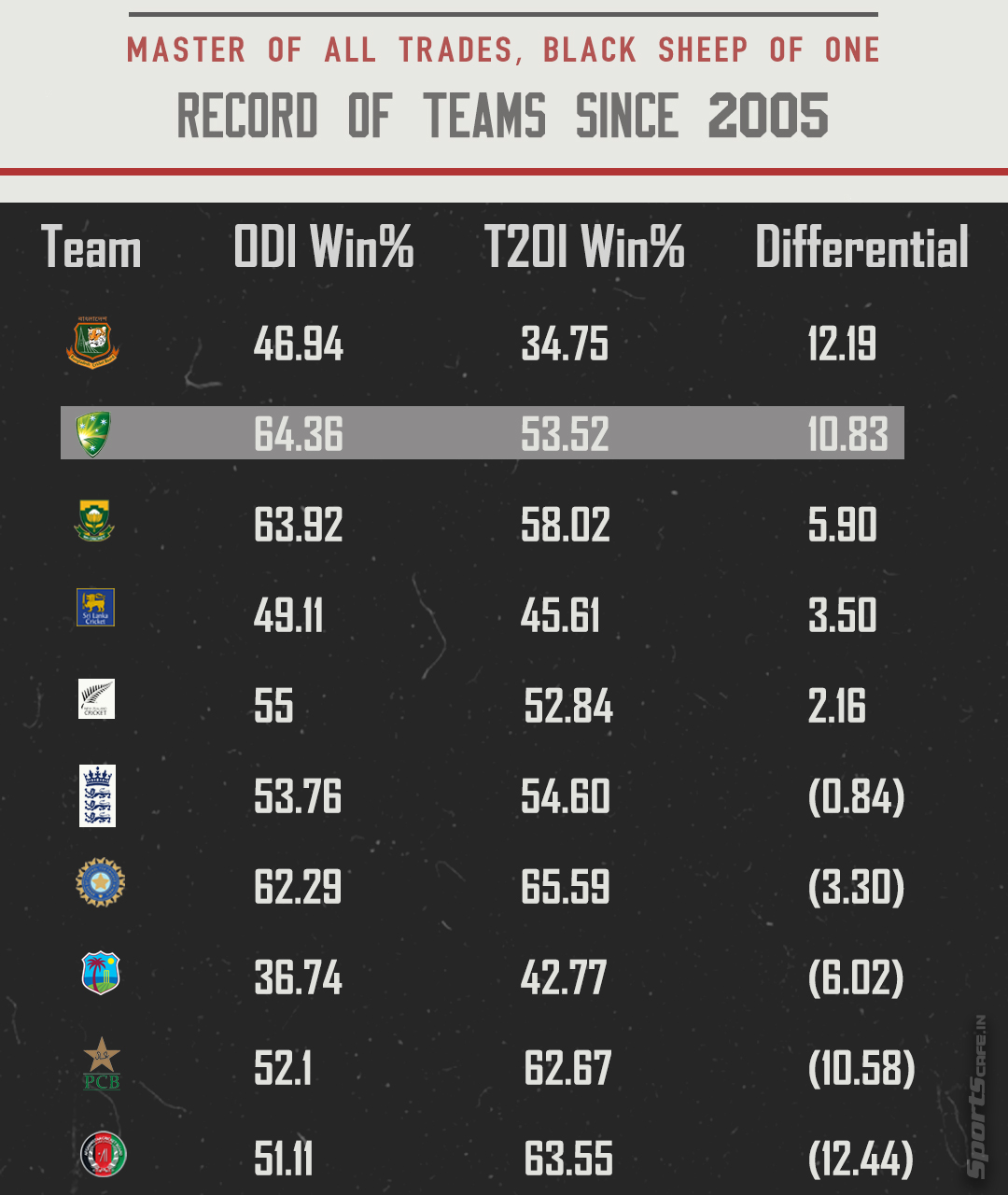

Yet, when it came to T20Is, the same confidence seemed to wane. In the longer formats, you could lose a phase or two but in the overall scheme of things, the quality more often than not shone through. But not here, not in the game of moments. T20 cricket condensed the entire sport and gave greater relevance to small but meaty contributions over sustained quality, thus challenging the entire hallmark of Australian success. Since 2005, Australia continue to have the best winning percentage in ODIs by a considerable margin. They have emerged triumphant in a commendable 65% of all their completed encounters – to put that number into context, all the other Test-playing nations have a combined success rate of just 44%, a remarkable 21-point difference. However, in the T20I standings, the Aussies rank a meagre sixth in the win/loss ratio department amongst the top ten, with better records than only Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, New Zealand and the West Indies.

There is a stark difference between Australia's records in ODIs and T20Is ©

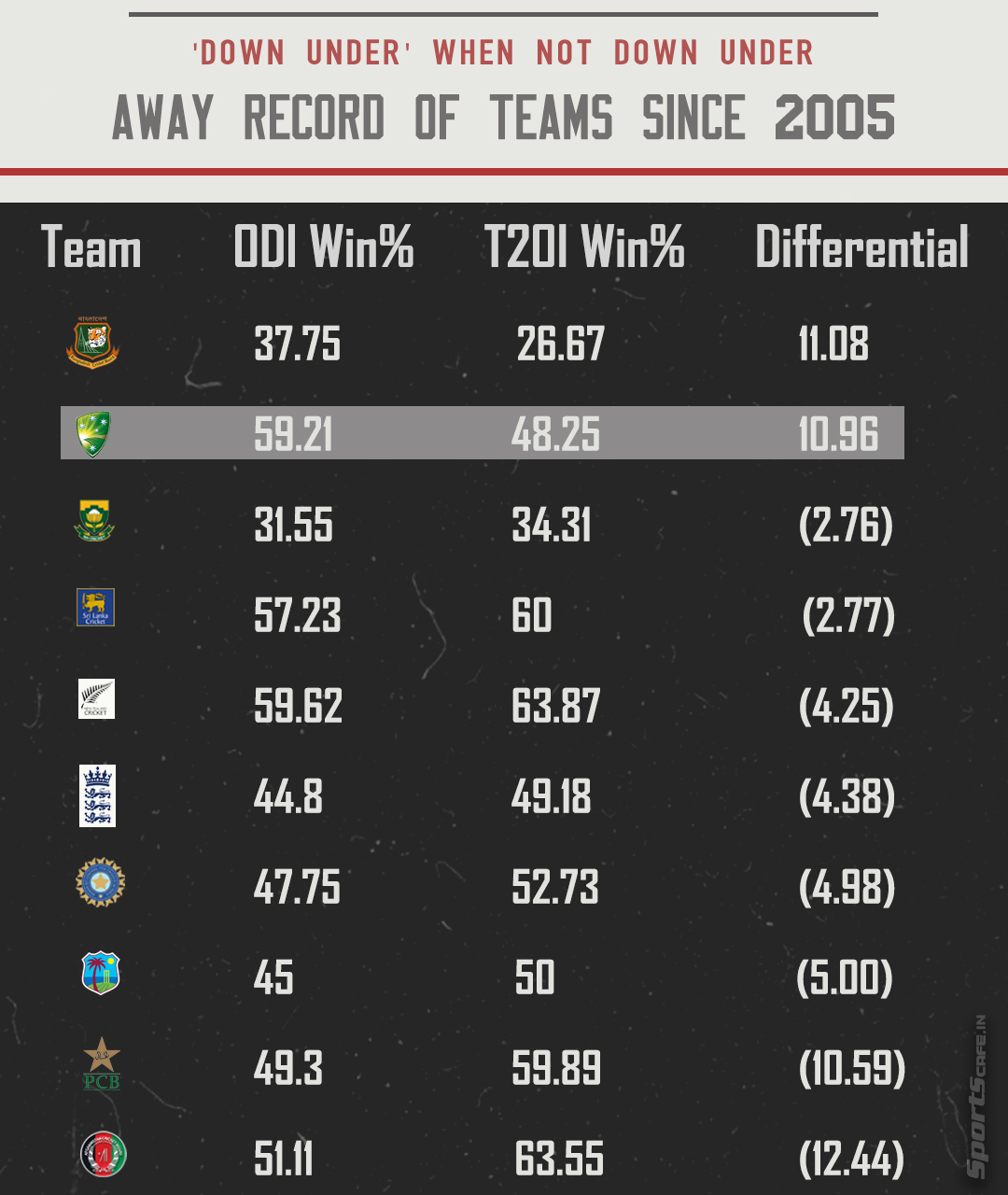

There is a stark difference between Australia's records in ODIs and T20Is © The fall from grace can at large be attributed to the Australians’ inability to adapt to foreign conditions and mould their teams accordingly in the shortest format of the game – an attribute they have historically prided themselves on. The Kangaroos have shown a clear reluctance to field specialist spinners through huge chunks of their T20I journey which has cost them big in the subcontinental conditions. Consequently, the team has lost more games than they have won away from their home island in T20Is, a statistic unheard of for Australia in cricket. What is even more mindboggling is the fact that in the same period, they have won over 66% of their away ODIs, even experiencing a significant uptick from their record in the previous decade where they emerged victorious in around 59% of their away clashes.

Australia were historically renowned to win regardless of conditions on offer -- until T20Is came along ©

Australia were historically renowned to win regardless of conditions on offer -- until T20Is came along © Could the team’s lackadaisical numbers be put down to just on field failures though? Over the years, the Green and Golden Army made it a habit to invade all their rivals in the cricketing fraternity and turn on the style with stunning displays of bravado. Yet, come T20s, and the switch had flicked. All of a sudden, they were not the all-conquering emperors anymore but an XI of mortals that could be overwhelmed time and again. The subdued subjects had rebelled and changed the game forever. When the vanquished couldn’t throw the Kangaroos off their throne, they simply built a new kingdom of their own where the royals just became one of them. The narrative that kickstarted with ‘Anybody but Australia for the Cup’ gave way to repeatedly ‘Rejoicing at Australia's exit’.

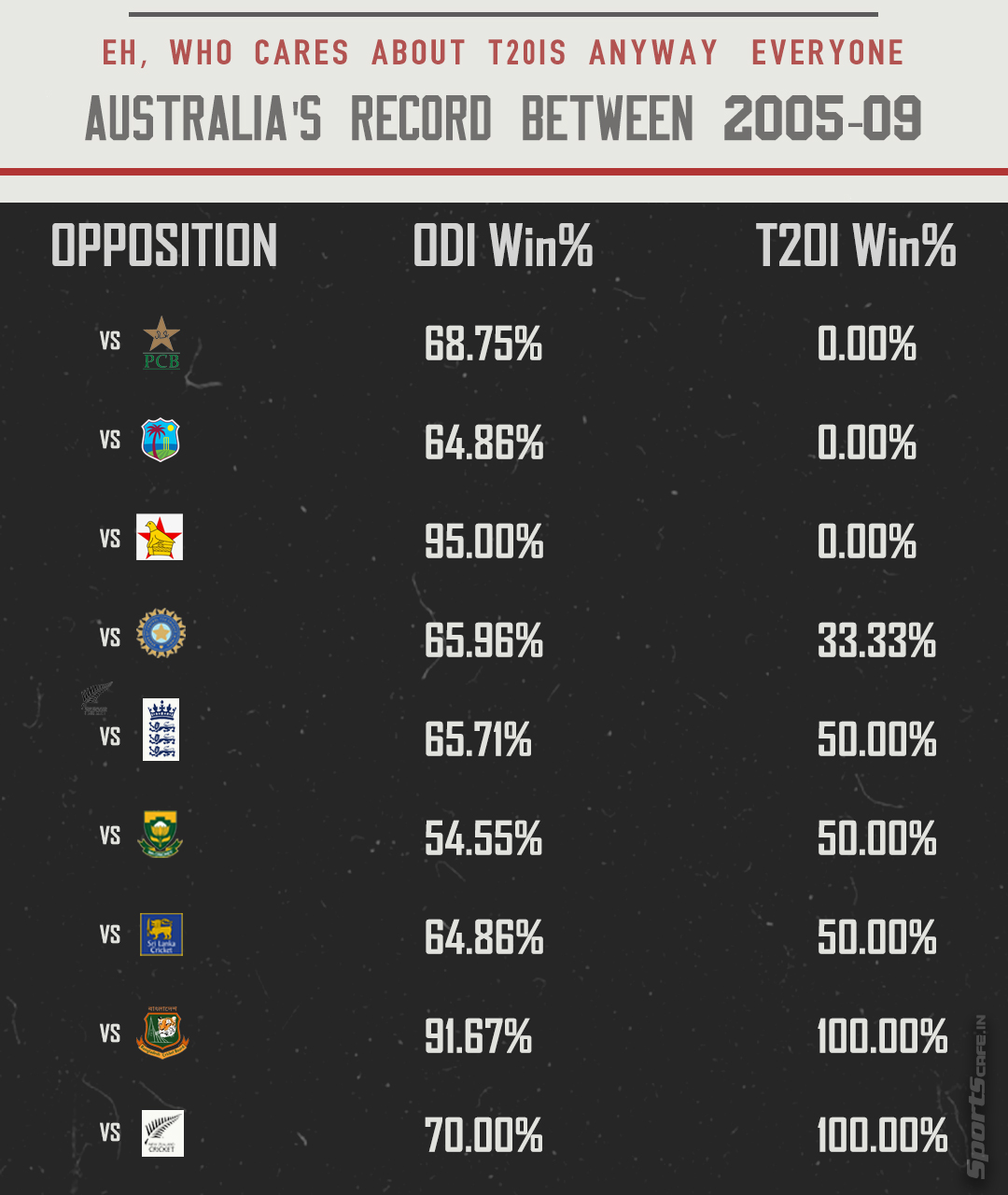

In ODIs, however, the power dynamics sustained. There was a clear emperor, and they had an advantageous record over all the rivals between 2005 and 2009. Yet, come T20s, and the Tigers and Kiwis were the only ones who bowed down to the fallen while the others rejoiced in vendetta. The Kangaroos even lost, the only T20I they played, to Zimbabwe – that too on the big stage, in a World T20. Clearly, the combatants in the cricketing fraternity had sniffed a chink in the armour and they were ready to shove in their spears.

Clearly, Australia took their own sweet time to take T20Is seriously ©

Clearly, Australia took their own sweet time to take T20Is seriously © After all, the other teams ironically had a clear headstart over one of the game’s pioneers when it came to T20s. Australia’s success in ODIs and Tests was in some ways driven by their spirit, legacy and long-term understanding of the game but all of a sudden, the tables were turned. While the others adopted T20 cricket organically without much ado, the men from Down Under refused to give it much importance. They time and again relied on a core of players that had had success in the other two formats to lead them to glory in the game’s newest innovation and were inevitably met with disappointment.

It should not have taken them long to realize Michael Clarke was not built for T20Is or that playing Brad Hogg as a specialist spinner would definitely reap more rewards than the part-time spin of Andrew Symonds in the 2007 World T20. Yet the Kangaroos insisted, persisted and dissipated. A panic-induced resort to T20I specialists did take place eventually after sub-par World Cup campaigns but it only saw a certain Cameron White become vice-captain, despite having represented them in less than 10 T20Is.

As a matter of fact, Australia continue to be plagued by a lack of T20I specialists in their squad despite having the second-most commercially successful and longest-running T20 franchise league globally. As if placing the Big Bash League bang in the middle of an all-important Test summer was not enough, the tournament has also failed to fast-track consistent domestic performers into the national squad. Given that Australian internationals don’t compete there regularly and even the homegrown talent receives no promotions, it is worth questioning the competition’s purpose from a cricketing standpoint. Other leagues around the world such as the IPL, PSL and BPL use their franchise competitions as feeders for the requirements of the country, then what prevents Australia from doing so? The likes of Jonathan Wells, Tanveer Sangha and Alex Ross have time and again delivered commendable returns, yet are nowhere in the scheme of things when it comes to wearing the Baggy Gold.

In theory, the Big Bash League is the perfect platform for the side to adopt the model the English have used to excel in white-ball cricket over the past seven years, as much as that may be a metaphorical kick to their groin. The three-pronged solution is simple yet almost ridiculously effective, as showcased by their rivals’ recent World T20 triumph – establish a philosophy, stick to it throughout as a squad is built around the ideology regardless of temporary lulls, and most importantly, be brutal in dropping the non-performers.

Yet, the Aussies persist in a pattern earmarked by a lack of organized planning which evidently cost them in the recently concluded World T20. The fact that the management had no clue how to approach things was transparent in the way they treated Cameron Green. Transitioning him into a makeshift opener less than a month ahead of the marquee event and featuring him in pretty much every T20I was followed by not even including him in the squad for the major tournament. Now, heading into 2024, in their ranks they have a captain stuck on the fence, an ageing core and no T20Is scheduled for the next 9 months.

The only consolation for the team in their T20I history has been the triumph in the World T20 last year in the United Arab Emirates. A couple of mini-miracles there saw them somehow stumble to the trophy. Yet, it doesn’t need to be reiterated that the tournament witnessed one farcical result after another where the game’s fate was often dictated by the toss itself.

If the Australian attitude towards T20s since its introduction is anything to go by, the Kangaroos probably have a renewed confidence over their chances in the format which seems to definitely be unfounded. The Kangaroos continue to succeed in one way or another and build a legacy for themselves. But, the times have changed, and a new region of the world has opened up for the emperors to explore. They can choose to be content with their existing conquers but at the same time be wary that no longer will they be remembered as a dynasty. At the end of the day, it is now up to the Kangaroos whether they consciously build towards a better future, or let a few lucky coin flips dictate the legacy of the greatest empire cricket has ever seen.

Comments

Sign up or log in to your account to leave comments and reactions

0 Comments